Extensible Meaning in a Shared Cloud

This post describes possible data formats and network protocols for implementing Overlaid Personal Semantic Networks (OPSN), or any similar scheme in which many people contribute to a common pool of data (with general and extensible meaning), and each person stores (and can republish) the subset they’re interested in.

It describes how a formal vocabulary for defining data’s meaning can be reliably extended by anyone without central coordination, with the community able to disambiguate symbols and expressions as needed using the mechanisms of OPSN.

(It does not propose specific symbol meanings (for OPSN or any other purpose); rather, it tries to ensure that those can be experimented with, so any subcommunity of users can improve them over time, and multiple communities could do this differently in one common network, without interference – they can use each other’s work as they see fit.)

It also covers the technical and legal features which are essential for users of different software platforms to effectively view data within one unified graph (a “shared cloud”, since the data is not tied to specific hosts, or even to specific platforms) – free copying/rehosting of data in a “universal format”, without losing its unique addressability or its connections to other data. (The same features permit data to be reliably archivable with long-lasting references.)

A companion post [UNFINISHED, not yet posted] addresses details of data storage and communication, describing requirements for a minimal protocol, but also how existing systems and data formats can be accommodated, so existing and new systems can work together to implement the desired network. (Some “advanced topics” and other companion posts are listed at the end, including one that suggests prototype projects which apply these ideas to OPSN or other purposes.)

(This is intended to be a motivated high-level description; it doesn’t contain a specific low-level proposal, but it can be read as a set of requirements for one. As usual, I make no claim of originality for most of the specific ideas used here; in fact, many of them are well-known. (I think the way they are combined here, and the set of properties gained from this, are original, though.) I have tried to credit the non-well-known but non-original ideas at the end, or where they are referenced.)

logical structure – each person knows a set of things

The basic idea of OPSN (as described in a Social Network for Ideas) is to imitate the natural discussion system of a group of people, modelled as the public parts of a set of semantic networks (one per person) which grow and change during the discussion, with each person learning the parts of the others’ networks they’re interested in.

To design a corresponding distributed data structure (including data formats and storage policies) and network protocol, we start by describing the involved data as simply as possible:

-

each person knows a set of things (has a pool of items), described using a set of common terms (symbols);

-

those items can be communicated to other people (being added to their pools of items, in some cases after modification to indicate their proximate source);

-

each person’s pool of items changes over time (mostly growing);

-

each person can make up new items and/or new symbols;

-

some items describe connections between other items, or metainfo about other items.

-

I use the term “know” (about items in a person’s pool) for convenience of description – not to imply that each item represents a statement, or (when it does) that each person who has that item believes its statement. I’m calling the “known things” “items” rather than “statements” to be neutral about the kind of meaning they have, if any. So (for most items) the only belief implied by “knowing an item” is that the item’s uid maps to its content (this will be defined more precisely below). When we do need to represent actual belief in a statement (as opposed to mere knowledge that an item exists), we’ll need an item whose existence (in our pool, or anywhere, depending on its type) implies something like “person P believes statement S” (see the advanced topic posts about “expr meaning” and “signing statements” [the 2nd one is UNFINISHED]).

(There is also a lower-level sense in which every item can be treated as a formal statement (about its own data and uid), explained in “expr meaning”.)

Also, the term “person” does not imply one-to-one correspondence with actual people, each of whom might create multiple identities for social reasons, and/or multiple pools of known items for implementation reasons (or might share identities or pools with other people). To keep things simple I’m just considering that obvious, and ignoring it in what follows, so “person” below just means (according to context) a single identity for authoring items or signing statements, and/or the owner of a single pool of known items.

How items refer to other items will be discussed below; for now I’ll just say that every item or symbol has a universal identifier or uid which can be used to refer to it, and which is based on an unchanging part of its definition or content rather than on where it’s stored (which might be in more than one place, and might change over time). (Note that this is not a “user id” (though Unix uses the same term “uid” for that), nor is it the same as a UUID, which is a specific but more limited format with related goals. It could be considered a kind of URN, if that term is interpreted generically rather than as implying any specific syntax or standardization status.)

immutable data (which might represent mutable items)

As a basic simplification, we’ll assume each “primitive item” (an item directly present in someone’s pool of knowledge) is immutable; to represent a mutable item, we’ll make primitive items which define its history (and any inter-person variation in its value). To represent changing the mutable item, or weighing in on a conflict about its value, a person will add new primitive items which formally say they’re doing that. In that way the basic protocol need only consider propagation and collection of immutable items. (How to interpret those items can be left up to the client code which uses the protocol, though we discuss that here too.)

The term “item” itself is too general to imply immutability in all contexts; when we need to be explicit we’ll say “mutable item” (or “mitem”), or call an item “primitive” or “immutable”.

There are a few types of mutable items we need to consider:

-

each person’s pool of known items as a whole (a set, which changes when items are added or (occasionally) removed);

-

other per-person variables (such as various kinds of formal opinions about other items – e.g. this is how an item’s topic-tags, or its belief or endorsement status, can be person- and time-dependent);

-

a “growing file”, representing a stream of incremental changes to a set of items or other per-person variables (always a linear stream with no inter-person conflicts, since it has only one author even if it’s republished);

-

a “shared mutable item” or “mitem” (pronounced “emm-item”), a subject of collaborative work within this system (e.g. a “wiki page”, or any other shared editable state – one tag on one item is a special case), which exists only as described by various people’s statements about it within the network, and whose current state thus depends on both person (or point of view) and time, and might not always be consistent. OPSN does not specify a single preferred way to implement an mitem – rather, an mitem’s original declaration defines its id (an “muid” or “mutable-item uid”) as identifying an mitem implemented according to a specified distributed algorithm. This allows all client software to see which (primitive) items are statements about a given mitem, even if it can’t implement that mitem’s particular algorithm. If it can implement it, then it knows how to resolve that mitem’s current value, and how to create new primitive items (as formal statements about that mitem) which will be interpreted as its person proposing/endorsing/declaring a specific change in that mitem’s value, or a specific way to resolve a conflict.

(We don’t call the above kinds of mutable items “objects”, partly to avoid confusion with objects in the implementing software (since each mitem, being persistent and distributed, may be implemented by many objects, especially in different computers or over time), and partly since their nature is different – mitems are inherently nonlocalized and transparent.)

item removal is non-primitive

Another simplification is to consider item removal to be nonprimitive. Specifically, if someone thinks item I should be removed for reason R, they’ll publish a fancier item saying so, which recipients can receive and pass on in the normal way, and additionally recognize and act on (by considering removing I from their own database, and/or refraining from passing it on or from serving it on request, based on R and their own policies).

Thus the basic protocol need only consider passing on new items (to subscribers to a pool’s changes) and adding them to pools. (To permit certain optimizations, we also allow requesting specific items from pools, but the fact that this might fail due to item removal need not extend the network protocol, since it could have failed for other reasons.)

universal format for item data

As another simplification, we’ll assume items are represented in a “universal data format”, so each item can be copied unchanged from one pool to another (when desired), preserving its meaning (at least to the extent that its symbols are unambiguous in meaning). (If someone wants to store items in a localized format, requiring other kinds of transformation when they’re copied, we consider that an optimization which should be done transparently. Also, the fact that we can copy an item doesn’t mean we should, especially if it’s a statement being copied into something’s “set of beliefs”; this is discussed in “expr meaning”.)

Note that the “item meaning” I refer to here is not the meaning of natural-language text in the item data (which can’t yet be formalized, and might be different in detail for every reader even when the text is the same), but the meaning of internal symbols used to represent an item as data, such as data format symbols which mean things like “this is text” or “this is an image in format F”. Where these concepts start to overlap is in the meaning of relation symbols, such as “this item is arguing against (the view described by) that item”, or item predicate symbols like “this item is a statement (about the world)”, which are used in the items which indicate people’s opinions about other items.

All these classes of symbols need to be extensible, so any user or subcommunity can define new symbols, without waiting for other users’ client code to accept them, and thus experiment with enhancements to how the system classifies and understands relations, or add new basic datatypes (like math or executable programs). Of course this means that any particular client code might encounter format and relation symbols it doesn’t understand; in general such symbols can be defined as belonging to an “abstract class” which the client does understand, allowing it to handle them in a default way (for example, safely ignore them or pass them on unchanged, or act as if they were better-known symbols).

By a “data format” (for items or parts of them), we mean not only a “syntax” (or binary format), but a map from data to meaning (also depending on the meanings of any symbols used in the data). (Such a map can’t generally be formalized (except in the important special case when the “meaning” is just another kind of data), but it is an important idealized construct for talking about data formats and transformations between them.)

By “universal”, for a system or protocol or format for data, symbols, references, ids, etc, we mean whichever is applicable of “its representations are interpretable independently of time and context”, and “it’s general enough to be used in place of anything of the same kind (with appropriate translation)” (like a “universal computer”, or an operation defined by a “universal property” in category theory). If two formats or systems, developed independently for the same goals, both deserve to be called universal, it will always be possible to translate between them and thereby use them together.

Having a universal item format requires:

-

the symbols in items (analogous to words in formal text) must also be universal – i.e. unambiguous in identity, and in “official definition” (and thus, by convention, in “official meaning”), even though their “meaning in practice” is unavoidably dependent on usage and must therefore be subject to discussion (and symbols will often need to be “forked” for disambiguation);

-

every item must start with a symbol which implies the rest of its internal format, and (at least implicitly) the map from its data to its meaning (and thus restricts its possible meanings);

-

items must refer to other items in a universal way (independent of time, and of the context or location of either item);

-

anyone can extend the possible meanings or internal formats of items (by making up new symbols for use in them, and specifying their “official definitions” in a way that any future user of the symbol can reliably determine).

universal expression

The simplest general format which meets those needs is some kind of “expression”. (We sometimes call an expression an “expr”, and a universal-format expression a “universal expr” or “uexpr”.) Its low-level syntax (or binary format) doesn’t matter much – it could be a specialization of JSON, XML, S-expressions, some new syntax (textual or binary), or “any of the above” (as long as the acceptable syntax/format is documented precisely) – though as far as I know (see the “comparison” sections below for details), no existing standard format has good enough standard rules for universal interpretation (when we want possible meanings to be general and reliably extensible in a decentralized way), so we have to specify those ourselves. (But we’re allowed to specify them for a restricted subset of a standard format (and require its usage) if it makes things easier.)

(For interpreting “external data” (like the contents of an emailed or http-served file) as one or more OPSN items, we’d like a more general format than the one for items “already in OPSN”; see the advanced topic “universal document format”. [UNFINISHED])

Any expression format defines a recursive datatype in which expressions are built up from smaller expressions and “atoms” (symbols, numbers, references, etc). More precisely, each expression is either an atom or a “compound expression”, which has a “combining symbol” (sometimes called “operator”, “constructor”, or “head”; in some syntaxes this can be an expr, the “combining expr”) and zero or more “argument exprs” (sometimes called “arguments”). (Any expression inside a larger one can also be called a “subexpression” or “subexpr” of the larger one.)

An expr’s meaning is also defined recursively using this structure – in general, the combining symbol’s meaning should be a function from the “tuple” of argument meanings to the expr’s meaning. (For details, exceptions, potential problems, and practical considerations, see the advanced topic “expr meaning”.)

(As is well-known, exprs can conveniently represent any data structure used in computing or saved in files. For example, any kind of “record” or “serialized object” can be represented by defining a symbol to use as its constructor, and other constructors can be defined for forming lists, sets, graphs, etc. And of course exprs can represent expressions (or whatever those expressions represent) in any formal language (such as math notation, or a programming language, or a grammar or transformation rule) – that’s what they were named after and inspired by. So there is no problem defining expr-based formats for any kind of data – in fact, most new formats only require shallow exprs and a few custom symbols. Most importantly, as long as new symbols can be defined (and their meaning specified in a general way), all expr formats can represent the same things, regardless of their low-level syntax or binary format.)

If an expr format is to be universal, each of its components also needs a universal format – in particular, we need a universal format for symbols and for item references.

We’ll start with the fundamental case of symbols (also delving into how the community can disambiguate symbols or correct “errors in definition”, and how users manage changes of all kinds to items they depend on for defining meaning); then generalize to immutable item (or data) references; and finally cover shared mutable items (whose full implementation is complex, but just defining references to them can be a straightforward extension).

universal symbol

A universal format for symbols needs three basic properties:

-

the symbol referred to is unambiguous;

-

anyone can make up a new symbol, and (at least by convention) define its “official meaning” (in a way which any user of the symbol can reliably determine);

-

any user can effectively treat certain symbols as being equivalent.

The simplest scheme which provides those properties is for each symbol to be represented (essentially) by a cryptographic hash of its “defining data” (which we must ensure can be looked up given the hash, by anyone encountering the symbol), where the defining data includes the symbol’s “official definition” (which often needs to be informal), and any other “defining metainfo” its author wants all users of the symbol to have (e.g. author identity, formal definitions (if any are available), or hints about recommended behavior when the symbol is not specifically recognized by client code, e.g. an “abstract class”). The defining data should also state its own intended purpose (i.e. being defining data for this kind of symbol definition), and refer to documentation of the definition format, pointing out the implied license to copy and use the data – more on this below.

(The defining data must be represented as an array of bytes (“octets”), to be suitable input for a standard hash function, so we also have to specify a serialized format for it.)

(To preview how we’ll generalize this scheme to refer to immutable item data instead of a symbol: use different defining data, including a modified statement of purpose, and the item data or its hash.)

(If two people accidently defined symbols using the same exact wording of official definition, and left out any metainfo that might distinguish them, they’d get the same identical symbol, but that would be ok. (If the symbol was for a well-known term, it might even be what they wanted.) If one of them wants to avoid this, all they need to do is include unique metainfo, like their name, the creation time or context, and/or a random number.)

The cryptographic hash value (plus some formatting to make its nature clear, e.g. to name the hash function or mark it as part of this symbol format) then serves as the symbol’s uid (universal identifier), and as the main (usually only) part of a reference to or representation of the symbol. (Note that for a symbol (as opposed to data), reference and representation can be the same – when a “use/mention” distinction is needed, it can come from the context; routine uses of a symbol can proceed without ever looking up its defining data. The defining data’s purpose is to guide discussion of human users considering whether or how to use the symbol, e.g. when implementing new rules for making or handling data that contains the symbol.)

As for equivalent symbols, purported equivalences can be discussed by multiple users along with all other symbol and item properties, such as the ones needed to support “disambiguation” as discussed below; OPSN mechanisms can be used to keep updated each user’s or subcommunity’s opinions about these. The results should then affect the operation of that user’s software when it handles exprs which use those symbols. Whether to make replacements of equivalent symbols when copying otherwise-unchanged exprs (as opposed to only simulating those replacements when interpreting the exprs) is up to each user’s software. Sometimes it’s better to avoid replacements, in case other users, or the same user in the future, have different opinions about the equivalence; other times it’s better to do the replacement, when the new symbol is better known, either in each occurrence, or by making a larger expr which defines a local context (as discussed elsewhere). This should be mostly decided automatically, but the detailed rules governing that (and related rules governing disambiguation) will need to be developed as experience is gained, and remain under per-user control.

why it works

The symbol-representation scheme described above provides no way for the author (or anyone else) to prove who made the symbol – that can be documented in the included metainfo, but is not verifiable. But, when combined with a reasonable convention, it does allow proof that the symbol is a symbol and has the claimed official definition (and thus, informal proof that it has the corresponding official meaning). The convention is simply that “anything which uses this format is this kind of symbol, and its official meaning is, by definition, the meaning described by the official definition in its defining data”. (Whether the official definition is clear or even makes sense, not to mention how it relates to what the author had in mind or to the symbol’s “meaning in practice”, are other matters, discussed below.)

To see why this works, consider someone trying to “fake a symbol” – to make one which says it has official meaning M1 but actually has official meaning M2 (or has a nonsense definition, or is not a symbol of this kind at all). To fake it, given this convention, they have no choice but to hash some data which says it’s being used this way and has an official definition with meaning M1.

But then, by definition and this convention, they have in fact created an actual symbol of this kind with official meaning M1, even if they claim they didn’t (or believe they didn’t).

If someone creates a symbol, and later realizes it has a different meaning than they intended (e.g. if they realize they misunderstood the official definition they used to make it), they should just create a new symbol. Documenting their error in creating the first symbol might be useful (since it suggests that some uses of it might have the same error, so it ought to be “disambiguated” as described below), but (by this same convention) it won’t “correct” the first symbol’s official meaning. In fact, the reliability properties we want require that nothing done after creating a symbol can alter its official meaning.

It’s also important that a valid symbol of this kind won’t be made by accident (except with negligible probability), and more generally, that for any particular fully-specified version of this scheme, its symbols can’t be confused with symbols made by a different scheme (not even a differently-fully-specified version of this same scheme). (The latter property is not strictly needed for universality, but makes it much easier, since it means symbols made by multiple schemes of this kind can be unambiguously mixed together without marking which scheme they came from.)

To make this true is the reason we said above that the defining data “should also state its own intended purpose”, and that it should refer to documentation of its (fully-specified) definition format (for example by mentioning the title and hash (and perhaps the date and a URL) of a public document that describes it – not just the document you’re reading now, but one that spells out a precise format which implements these ideas).

Finally, we need to make sure that anyone encountering the symbol will be able to find its definition, use the symbol in items they publish, and make modified versions of the symbol. This has both technical and legal components:

-

the symbol author and reusers (or at least some of them, at any given time) need to keep its defining data and provide it on request (given its hash), and/or publish “location hints” (described elsewhere) about where that data can be found;

-

the symbol’s defining data should explicitly permit the actions needed for these uses, such as modifying the defining data and incorporating that into a new symbol (as discussed in the next section), by containing or referring to a license (perhaps via the reference to the definition scheme’s documentation) which explicitly allows those uses and actions.

correcting ambiguous definitions (and making other improvements)

Of course, though you can’t “fake a symbol”, nothing prevents you from making a real one which is ambiguously or otherwise poorly defined. Worse, you might make it correctly, but then you or some other community might use it incorrectly (and encode that use into functioning software, perhaps inconsistently in different implementations) – and in practice a symbol gets its meaning more from how it’s being used than from its official definition. Even once the problem is discovered, the incorrect usage (perhaps by then built into community practices and software tools) can result in incentives and pressure to keep using the symbol in the same (officially incorrect) way. (In the evolution of natural languages this even happens on purpose (with new slang); but even in languages intended to be formal and stable, like math notation or programming languages or data formats like HTML, there are well-known occurrences of this problem, enough that it should be considered normal rather than exceptional.)

Fortunately there is a solution to this, formalized in OPSN (with precedent in Wikipedia page-naming), but inspired just by common practice as any natural language or jargon evolves. Namely, when anyone notices an ambiguity, whether as a difference between different ways a symbol is being used, between its usage and official definition, or just between what different people think that definition means, they are free to create new symbols, each resolving the ambiguity in a different explicit way, and to publish the formal opinion that the original symbol should be deprecated due to ambiguity, and each use (though not each “mention”) ought to be replaced by the most appropriate choice among the new symbols. (Whether other people agree with that is up to them; both the discussion and the replacement can proceed according to the general principles of OPSN, as described elsewhere.)

Whenever someone accepts that S1 is ambiguous, and thinks a particular instance of it ought to be replaced with S2 (or thinks the same thing for any other reason), they just propose that change (in a formal and mostly automated way, via their software) in whatever item that instance of S1 is part of; acceptance of this specific change (or not) also can be discussed according to OPSN, though in practice a user would usually set up policies letting their software accept such changes mostly automatically, e.g. they might have already accepted a proposed general rule like “replacing S1 with S2 can be done whenever suggested in this set of items” (or for more efficiency, they might use a rule which just reinterprets all uses of S1 as S2 within that set). Whatever rule they use for themselves, they also usually recommend to their “followers”, who can combine different influences according to the OPSN scheme, so the work of deciding how to respond to proposed changes can be effectively shared across a community.

(Correcting an item’s content is most straightforward when the item needing revision is mutable, but if not, the item can be deprecated and its replacement by an improved item recommended. If there is a formalized way to do this for a certain item, we can call that item “changeable” whether or not it’s mutable – but then we can just think about another item, actually mutable, which defines which version of the changeable item to use (and defines policies for changing it by recommending or accepting replacements), so this ends up being equivalent to the situation for a mutable item. As said earlier, the author of any mutable item can determine the algorithm used to resolve conflicts; this would also cover choice of preferences about how to handle various kinds of suggested changes to its content.)

(Much of this discussion applies to other kinds of changes as well, like proposed improvements to open source code. In general, more complex changes and change-policies can be represented by a combination of the items and actions discussed here; for example, there might be a mutable item containing all versions of the code of one project (like in a distributed version control repository), and for each way of picking a “best version to use” (for different purposes), there would be a shared mutable item (called a “variable”, since its datatype is simple) naming a specific version of that code, whose value users would recommend updating (usually to a newer version) from time to time. This would let the community maintain multiple versions of the code and concepts like “current stable version”, while letting each user retain full control over what version to use (even a personal custom version if desired), or track a specified person’s idea of “current stable version” if they preferred. Note that it would be straightforward for code in one project to make use of a component of a different project, as long as it specified a specific version (which would be upgraded by the developers of the first project, like any other change to their code). Normal OPSN caching behaviors would mean anyone using that code would have all other code needed to run it, even from different projects. In effect, all open source code in OPSN would be part of one big project, divided into subprojects for administration and maintenance and versioning, but usable as a whole (to the extent its parts were compatible, which would improve over time); but users would only need local copies of the parts they wanted to use.)

users decide which changes to accept (mostly automatically)

We discussed several kinds of changes above: making new symbols to resolve ambiguity, changing items so they use those symbols, and changing items for other reasons.

For all kinds of changes, it’s important for each user to be able to decide which changes to accept.

Often they’ll want to make automatic rules to make this easier. Those would be common in the same cases that today are handled by users accepting new versions of open source software – for example, some users would examine each change closely, and manually accept changes that looked ok or good to them, while others would usually just trust some “official maintainers” of the shared items involved, accepting any change they endorsed (but if multiple groups claimed to be the best maintainers, each user could choose whom to follow).

Automatic rules would be even more common for accepting changes to text (like on wiki pages), as opposed to changes to internal symbols or shared implementing code, like we’re mostly discussing here.

But an important property of OPSN is that whether to accept any changes, however trivial, into each user’s personal version of a changeable item, is in principle up to that user. Often they’ll want to (as automatically as practical); but if they ever want to be very careful about each change, or to accept no changes to certain items (such as items representing the code of software they depend on), they can; or they can create two pools which have different policies for accepting changes to the same items, and use them for different purposes.

(How much past history (old versions of items, and details of changes) to record is also up to each user. Whether they recorded it themselves or relied on other users to do so, they can use that history later (as long as someone recorded it) to review whatever changes they accepted, with the option of changing their mind.)

universal immutable item references

We discussed above how to make universal references to symbols. The same ideas can be applied almost unchanged to making universal references to data and immutable items.

Since we’re assuming item content data is in a universal format – which means its meaning (given those of its symbols) (and therefore its type, to the extent that matters) is implied by its data – the identity of any immutable item is determined only by identity of its content data.

(Two items which describe the same meaning differently, and thus have different content data and uids, are not considered identical. Whether any two items (or more precisely, what they mean) should be considered “equal” or “equivalent” is up to each user (or piece of code) who understands their meaning, but has no effect on the level of the protocol discussed in this document.)

That means almost everything we said above, about creating a universal symbol reference from the symbol’s defining data, also applies to creating an immutable item reference from the item data.

The only differences are:

-

The defining data for an immutable item should contain the item content data, in place of a symbol’s official definition and defining metainfo;

-

it should describe itself as the defining data for an immutable item (not for a symbol);

-

similarly, the item’s uid (a syntactically marked hash value, as before) should be marked differently, to indicate it refers to an immutable item rather than a symbol (so we’ll know this even when the data can’t be found, or before we retrieve it);

-

it is no longer correct to say “a reference is also a representation” (of the item or its data) – most uses of the item will require actually retrieving and using its data (after verifying it has the expected hash value, though for repeated uses we can cache the data and usually skip verifying it).

As an illustration of the last difference, consider “printing” or otherwise serializing an item containing immutable data, versus a reference to a universal symbol.

If the intended recipient was itself integrated into the OPSN system (with good access to the same caches as the serializing program), we could choose an “OPSN format” in which either an immutable item or a symbol could be serialized as just its uid.

But for a more typical recipient, which can’t assume access to the same cache or which needs the data in a more conventional format, we would serialize an item by retrieving all its data and emitting that in a known format; but a symbol would not be serialized as its defining data – either we’d use it to understand the type of other data (thus never serialize it directly), or we’d look it up in some “namespace” (a map from symbol uids to names (or vice versa)), chosen based on the output format and context, and serialize the name we found.

circular references

Note that the properties of cryptographic hashes mean that it’s impossible for hash-based “reference cycles” (involving only immutable data) to be created. Therefore the assumption above of item content being in universal format, needed to justify considering the described kind of reference to it as being universal, doesn’t make this a circular definition.

Mutable item content can participate in reference cycles, but this doesn’t matter (for that issue) since mutable data is not involved in making those references well-defined (as we’ll see in the next section).

(It’s also possible to define symbols which indirectly refer to each other in a cyclic way, using well-known “self-reference” tricks to make each one’s defining data say how to compute the defining data of all of them. This might be useful, but has no effect on the issue discussed in this section.)

mutable item references

Finally, we can extend the above ideas to cover references to shared mutable items or “mitems” (which have already been discussed in several places above).

The basic idea is that for each mitem we want to represent, we make an immutable item which defines how it’s represented by telling us how to treat a growing but distributed subset of primitive (immutable) items as constituting the mitem’s current state (as well as being a record of all its prior and possibly person-specific states).

(Defining how an mitem is represented also defines the kind of data it can contain, which is often something more complex than a single value, e.g. a set or network of linked objects.)

(Note that this description of mitems is in terms of the entire OPSN system, a union of many users and many distributed pools of primitive items, not in terms of a single user or pool. The actions to be taken by individual users (via their OPSN client code) can be derived from this description. The act of making a new mitem would be done by a single user; its effects will spread to everyone interested (in the standard way defined by OPSN). Depending on the mitem’s algorithm (as discussed below), acts of changing it, adding to it, or resolving conflicts in its value, could be taken by the same or other users, with their effects similarly spreading.)

Specifically, the shared mutable item’s uid (or “muid”) can just be a symbol, which (unlike many symbols) has a formal definition (in its defining data), namely a small expression which contains:

-

a constructor for this expression format and meaning (i.e. a specific symbol) – this tells us the new symbol acts as an muid;

-

a symbol, newly made for this mitem, which marks the primitive items which together describe its state (by occurring properly in their own formal defining exprs – if desired we could reuse the muid symbol for this);

-

a symbol or expression which names or describes the algorithm to be used to implement this mitem (more on this below);

-

any metainfo the author wants to include.

What an mitem algorithm needs to do includes:

-

interpret current state (relative to a user and primitive item pool);

-

change state, or endorse or protest another user’s change (or make fancier kinds of formal comments on it), on behalf of a user;

-

detect conflicts (inconsistent values), and help the user and system resolve them, either by

-

making values consistent again, or

-

forking the mitem;

-

-

help merge previously forked mitems.

In early implementations of OPSN, we presume there would be a few available mitem algorithms, built into client code and named by their own symbols (whose uids and defining data would also be built into client code, as with all “built-in symbols” it needed).

Someday, when OPSN has been extended to understand exprs which can describe general code that most clients can run safely and correctly (by users defining symbols for representing such code, and convincing other users to adopt client code that can run it), new mitems can be made which describe their own algorithm rather than having to use a built-in algorithm (which may or may not be available in all client code).

The study of algorithms related to mitems is a well-known topic (though not under that name) – any algorithm related to “distributed state” or “distributed objects” might be adapted for use here, including those of existing systems for distributed version control or realtime collaborative editing. Some simple example algorithms are described in the advanced topic post “sketch of mitem algorithms”.

advanced topics

Some “advanced topics” are described in companion posts, to keep this post from getting too long.

References:

-

metainfo in a reference – a reference can come with info that’s useful before you follow it, like a hint about location, size, or license

-

reference to external data – like an item reference, but refers to raw data (whether or not it would make sense as item data)

-

reference to external object – a symbol or expr can refer to an external object, by describing how to find it and interact with it; if it does so formally, it can help OPSN client code interact with the object

Meaning:

- expr meaning – principles and code – how meaning of expressions can be defined; what to do when that’s problematic (e.g. when different symbols in an expr disagree about what it means); when exprs representing formal statements should be “believed”, and how this relates to OPSN pools; how expr-processing code can be organized; how standard expr grammars can be treated like file formats, but are more flexible and combinable

Long-term reliability:

- moving to more secure hash functions – what to do when your cryptographic hash function looks like it might be compromised uncomfortably soon (which will always happen eventually)

Comparisons to other systems, and interoperation with them:

-

comparison to location-based object identity – items identified by immutable-content hash can be moved or copied without loss of connections, which gives data references (including symbol definitions) long-term reliability; this lets a unified graph (“shared cloud”) be distributed across software platforms and potentially last longer than the platforms do

-

comparison to “Semantic Web” – its definition references are URLs, which like all “location-based object identities” are not long-term reliable; their mutability and lack of forking convention are problems for programming even in the short term. In theory its problems could be fixed, for example with better URIs (and numerous mundane improvements). In the meantime (or if they’re never fixed), some interoperation is possible. Maybe the problems could be ignored for short-term prototyping, but this has limited usefulness.

-

comparison to centralized definition – decentralized definition will end up easier and more reliable, with robust long-term evolution and disambiguation, at the cost of more chaos – but the chaos can be dealt with, and we can coexist with conventional schemes, perhaps even adopting and disambiguating their symbols to take advantage of their benefits and existing vocabularies

-

(see also data storage and communication, listed below [UNFINISHED])

Mutable items:

- sketch of mitem algorithms – example algorithms for single- or multi-author mitems

Optional topics: [the UNFINISHED ones are not yet posted]

-

universal document format – how some external documents (like emailed files) can tell us how to interpret them within OPSN [UNFINISHED]

-

signing of statements – how cryptographic signatures fit in, and how to minimize the need for them (or do without them if necessary) [UNFINISHED]

-

general data and code exprs – exprs have benefits as a general data format; “code exprs” can gradually be developed into a universal representation of portable open-source code; OPSN would be a good place to store and discuss all that, but its exprs might be useful for data interchange and storage even before its discussion system is implemented

-

garbage collection – how to clean up what’s not worth keeping, or give it to someone who still wants it

-

avoiding cascading failure – any highly connected system has this risk, but it can be mitigated

other companion posts

Initial implementation:

-

data storage and communication – minimal features for a “pure OPSN” protocol, and how to extend it so that existing and new systems can work together to implement the desired network, using existing systems and data formats unchanged or with new features [UNFINISHED]

-

possible prototypes – sketches of simple systems that could be prototyped, either with an OPSN-like UI, or anything storing its data in the OPSN format and network [UNFINISHED]

-

example fully-specified format – one way of spelling out all the details (not yet implemented) [UNFINISHED]

credits

There is too much related work to try to mention it all here. Most of what I would credit if it was practical is already well known, with the possible exception of the newest work, such as IPFS, and certain ideas credited within the text (though there is probably much more related work I am not aware of). (Although the git distributed version control system is well known, the ideas used in its repository format might be less so, so I’ll also explicitly credit them here.)

I have also benefited from ideas of, and related discussions with, J. Storrs Hall, Eric Messick, and Mark S. Miller. I thank John Baez for helping me clarify a draft.

Anyone who wants to list related projects on the collaborative design wiki at GitHub, or in the collaborative design software Google+ Community, is welcome to do so.

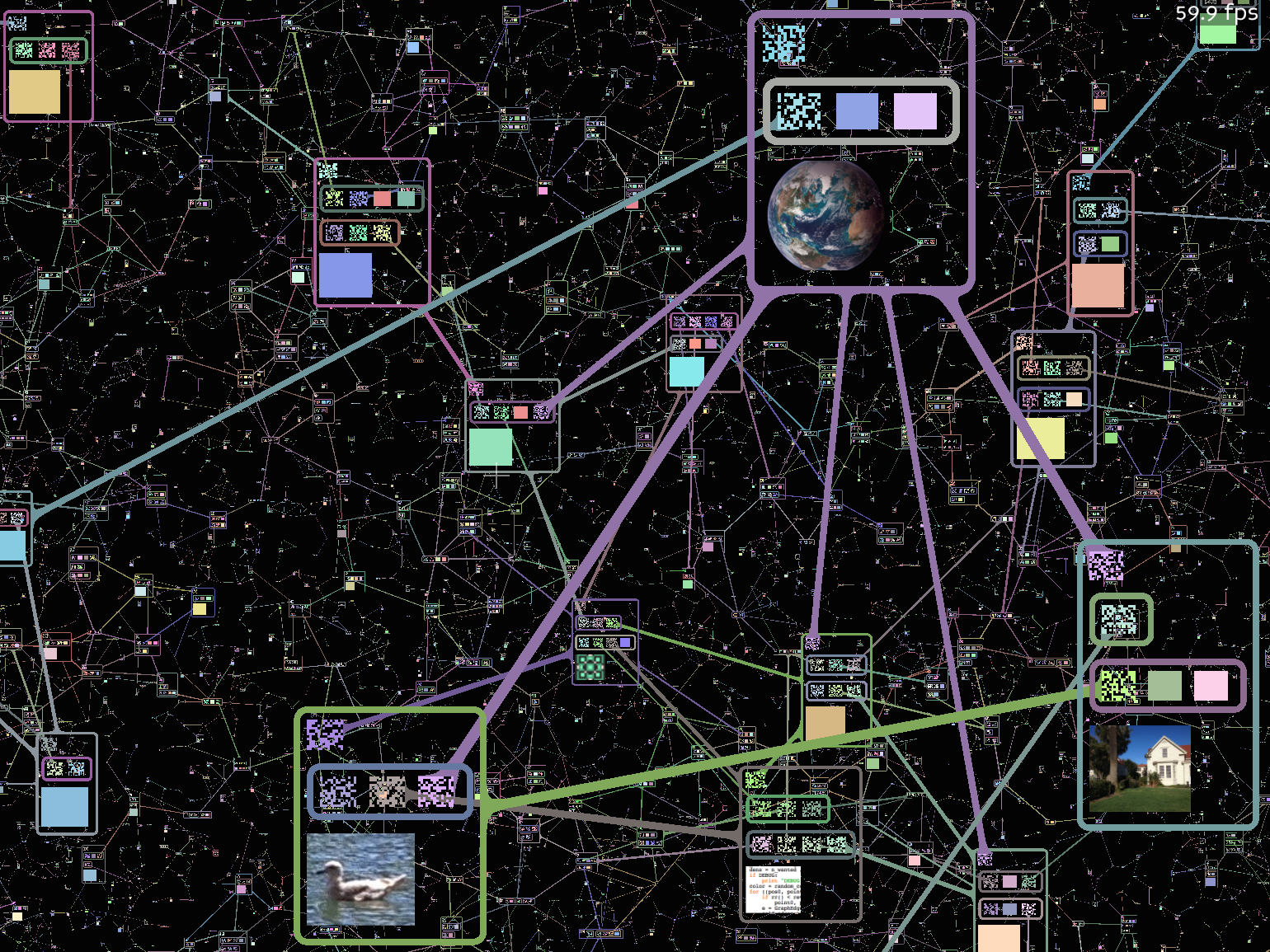

[Updates: 12/7/2015: added cover image and caption. 12/8/2015: posted to Google+.]

commenting

The best place to comment is on the associated Google+ post. (You can also comment there if you want to be notified when a specific “UNFINISHED” companion post is ready.)

comments

warning: Muut comments, below or in the Forum, are not fully deletable. Don't include private info. For unknown reasons, not everyone can see these comments. For other ways to comment, see the About page or use the corresponding Google+ post.